From Kirkus Reviews

“Readers who haven’t read Brown’s preceding volume, “Children in the City of Czars” (2023), certainly won’t be lost—Annie and Susan are both multilayered characters who share a wonderfully complicated relationship. Annie, in some ways, is a typical angst-ridden teen… but she is so affected by stress or anxiety that she becomes physically ill. While Susan is indisputably a loving and protective mom, she often rues the orphanage director’s warning: “This one is very difficult…” Much of the supporting cast, especially the males, are skeevy, incompetent, or a bit of both. What the villains are up to involves quite a few reprehensible men…Still, the mother-daughter dynamic is strong and fuels a convincing theme of family. Although this sequel provides a gratifying resolution, there’s plenty of potential material for another series installment.

A riveting tale of the seemingly unbreakable bonds of families.

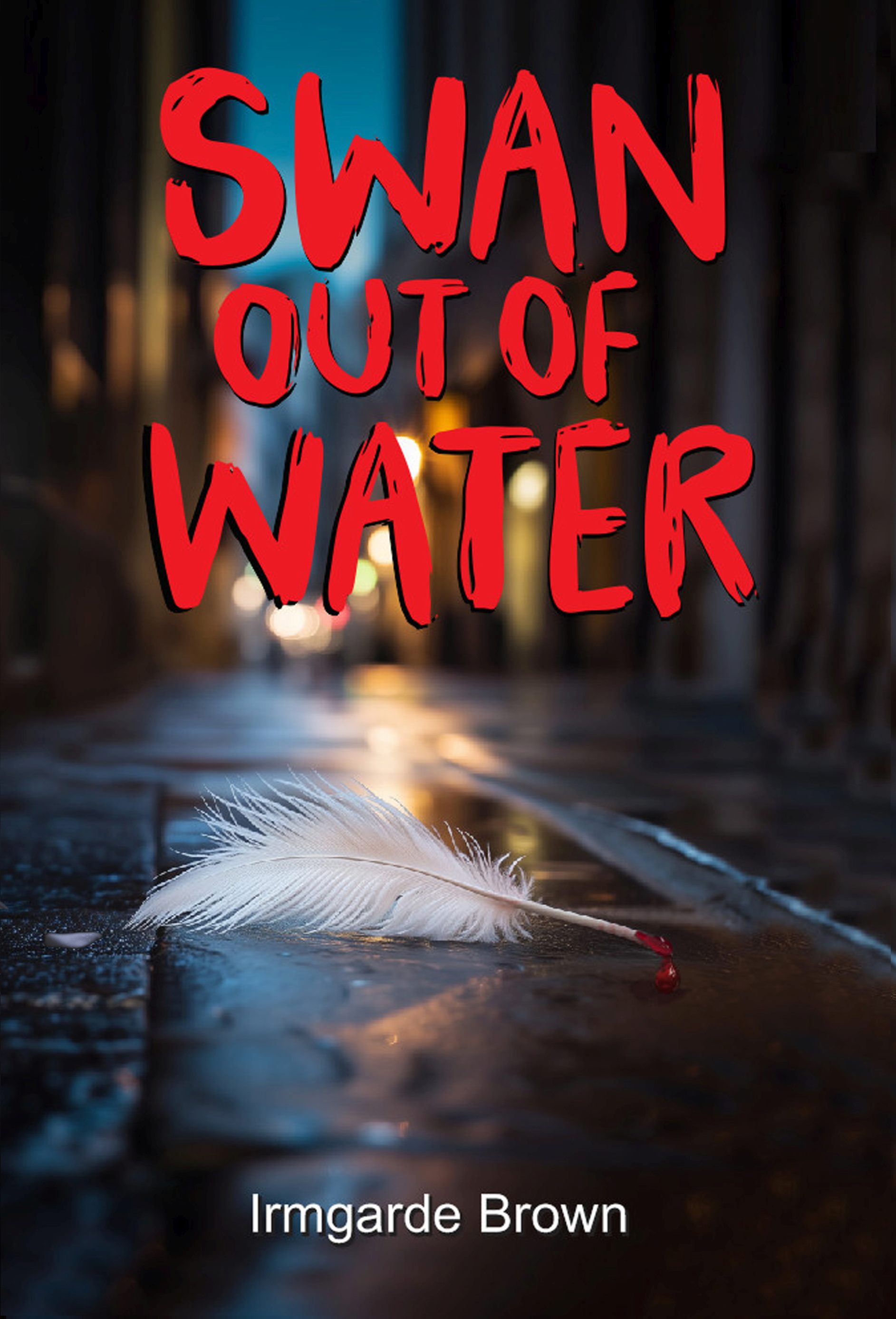

Brown (author of Children in the City of Czars) delivers a chilling, urgent cautionary tale of secrets, family, longing, and the men who live to take advantage of the vulnerable. In Maryland, fourteen-year-old Annie Spencer, adopted from Russia as a toddler, longs for friendship and a place to belong. When three girls—River, Shelly, and LaShonda—invite her to dance at parties inside a semi-truck fitted with arcade games and an audience voting for their favorites, the promise of easy money drowns out her mother’s warnings about these questionable companions. Soon Annie narrowly escapes a man who accosts her. Her friends are not so lucky. Reeling from tragedy, Annie is jolted when she uncovers her Russian adoption records and a devastating truth.

Determined to find her friends and to fund a trip to Russia and her birth family, Annie is drawn ever-deeper into a dangerous world, working for the mesmerizing Maks—who charms her with his Russian gallantry and warns “I have seen too many American parents brainwash their Russian adoptees”—and the cruel Lincoln, who has no compunctions about slapping a teen girl around if she asks too many questions. “Lying seemed to be the only way to get what she wanted,” Brown writes, and each small step Annie takes toward the sex-trafficking ring feels plausible for the character even as readers shake their heads no.

Annie’s job: recruiting other young girls at $200 a head. Brown examines how trauma and loneliness make Annie easy to manipulate, exploring in brisk, dialogue-driven scenes her naive belief she can handle these men, her willingness to believe Maks’ lies, and her eventual guilt about being an accessory to horrifying crimes.

Susan, meanwhile, surprises in her chapters, demonstrating deep concern and love that Annie can’t yet understand. The material is often bleak but never graphic, building to an upbeat, even sentimental ending. Brown reminds readers that predators often hide behind kindness, gifts, and promises—and that teenagers must be taught that these things are not love.

Takeaway: Humane drama of a teen adoptee longing to fit in—and the traffickers who prey on the vulnerable.