Who are the Orphans?

I am an orphan. But then, most people my age are. It’s the natural flow of life, children outlive their parents, and the baton is passed.

My father died when I was nine and apparently, in that moment, I became a “single orphan.” I didn’t know I had a label, but I certainly knew what it was like to be raised by a single mother. In some ways, it was for the best. My father was twenty-five years older than my mother, and I believe the speed of change for a non-English speaking older gentleman would have become more challenging than bearable. It was hard enough for mother to keep up, but she did keep up until 2004, dying at ninety-one.

Fortunately for me, my mother had already become the breadwinner in our household before my father passed and so I understood she had to go to work every day. Once again, I earned another label: latchkey child. To me, it was normal.

I write all this to say that single orphans usually roll with the punches, unless the remaining parent is damaged and unable to hold the family together, or worse, actually dispenses punches. It’s not easy to identify these kids until the bruises become blatantly obvious. In my case, my mother was merely unmedicated bi-polar. Hitting was rare, screaming was expected. I buried myself in books.

When it was time for me to have children, we discovered I was barren. In some circles, a shameful label, but one I finally accepted as we moved forward with adoption. We decided to adopt internationally and learned a lot about orphans, both single and double, or worse, abandoned by biological parents.

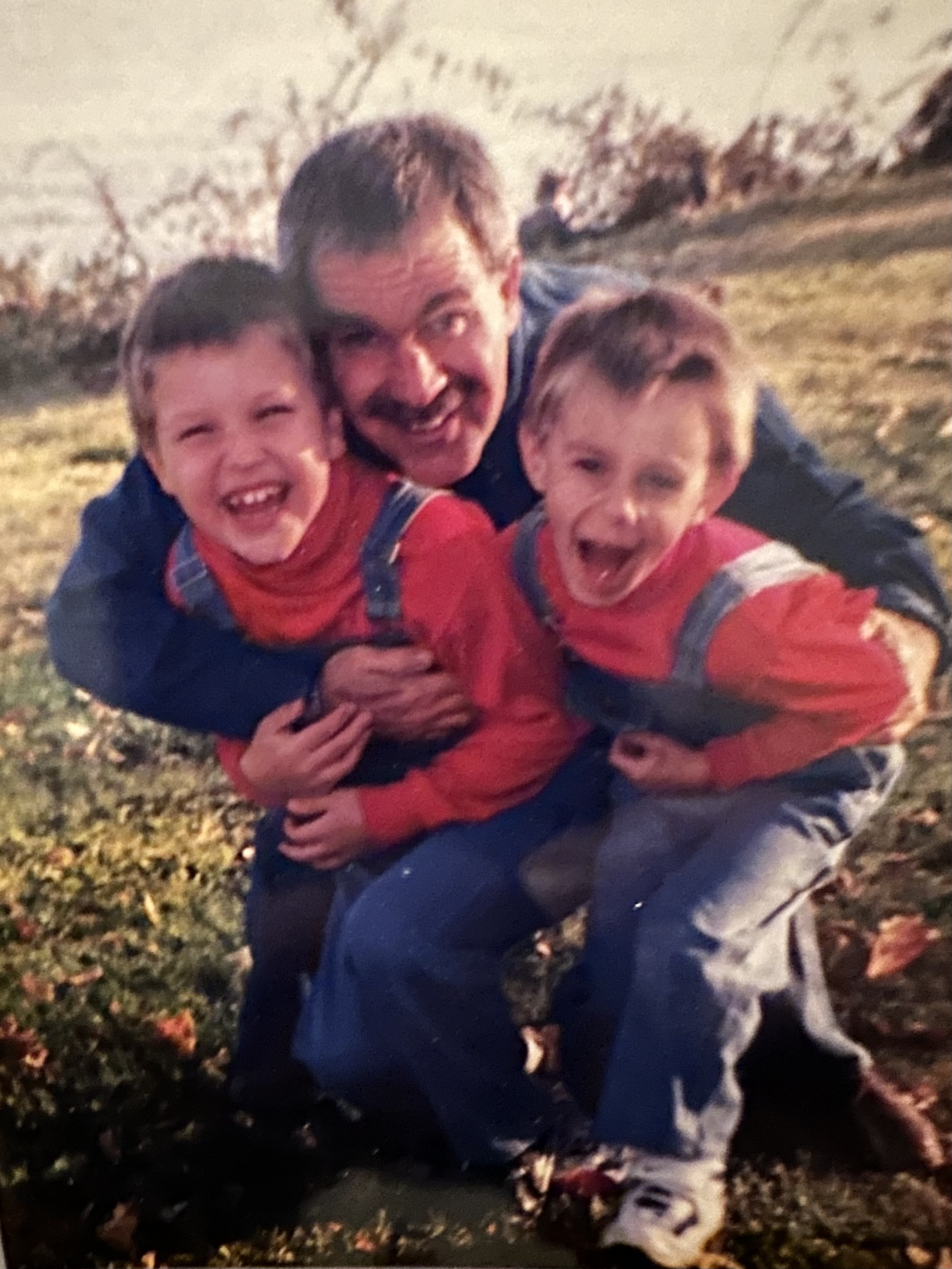

Our first adoptions were of two boys, aged four and five, not siblings but from the same orphanage in Latvia. One had been forsaken by his parents and found on the street and had been abused by a street gang. The younger one was a single orphan whose mother relinquished him at the hospital after multiple visits. Eight years later, we adopted a teenaged girl from St. Petersburg, a single orphan,

Our first adoptions were of two boys, aged four and five, not siblings but from the same orphanage in Latvia. One had been forsaken by his parents and found on the street and had been abused by a street gang. The younger one was a single orphan whose mother relinquished him at the hospital after multiple visits. Eight years later, we adopted a teenaged girl from St. Petersburg, a single orphan, whose mother was an alcoholic and father died of an overdose. She actually ran away from home at twelve, tired of finding her mother on the floor, passed out in her own vomit. In the end, the courts decreed the mother unfit and the teen crisis center where she had landed paved the way for her to be adopted overseas.

whose mother was an alcoholic and father died of an overdose. She actually ran away from home at twelve, tired of finding her mother on the floor, passed out in her own vomit. In the end, the courts decreed the mother unfit and the teen crisis center where she had landed paved the way for her to be adopted overseas.

During this time, my husband and I also visited and volunteered in two orphanages, one in Namibia and one in Zambia, Africa. The stories we learned there are too numerous to tell, but all are heartbreaking: deaths of parents, grandparents, aunts and uncles mostly by AIDS, but also alcoholism, drug abuse, mental instability and of course, abject poverty. These children were often passed from one adult family member to another, until eventually, there were no more adults to care for them. Neither of the countries where we served allowed foreigners to adopt. Most agencies in those countries work closely with local governments to help the children, but all the same, Zambia, for example has over million orphans.

I hope this little bit of background illuminates my interest and passion for orphans, particularly in Eastern Europe. My book, “Children in the City of Czars” is dedicated to my daughter who grew up in the city where this story is set. But in truth, I celebrate all children who have managed to navigate their difficult histories and thrive in spite of, or perhaps because of their adversities.